Marmitegate is just the tip of the iceberg says Nick Clegg. Even if you’re the most diehard Brexiteer it’s impossible to argue with him - unless you know nothing of how the food and drink industry works.

What’s less clear is how inflation will manifest itself. Lots of suppliers are already reporting significant increases in input costs. But inflation is at its most telling when it reaches the consumer. And judging by the hysteria that greeted even the prospect of a hike in the price of Marmite, consumers are going to hate it.

So the question is not will there be inflation, but when, how much, and where. At the IGD’s Big Debate retailers mostly dodged it. Only Tesco’s UK CEO Matt Davies gave any sense of the battle that lies ahead.

“As the number one food retailer, we are clear inflation is a bad, bad thing and we will do everything we can to make sure inflation is kept to a minimum. Everybody should be very clear how damaging it is to the economy, to retail and manufacturing businesses, and to millions of people struggling to live, week in, week out. All of our partners are very aware of how damaging inflation is. We’re working constructively on that.”

As we’ve seen, Tesco has quickly rebuilt bridges with Unilever, coming out of the affair with its (formerly tarnished) reputation as a champion of the consumer enhanced. But what happens to other negotiations?

Grocery Code Adjudicator Christine Tacon has been arguing that retailers cannot ignore calls for price hikes - particularly in cases where retailers had demanded and received price cuts from suppliers when sterling strengthened against the euro (from 2013 to 2016). Dave Lewis has effectively said the same thing: that Tesco will be more sympathetic if suppliers cut prices when sterling was strong.

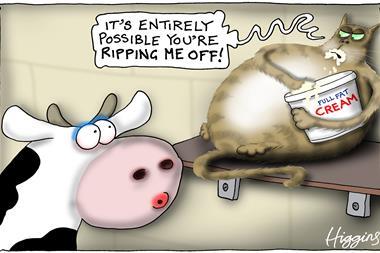

But Tesco has worked incredibly hard to become price competitive - even winning share back from the discounters - and it won’t want to give up those hard-fought gains easily. So, as well as watching its rivals like a hawk it will also be playing a game of bluff with its suppliers, particularly when it comes to hedging. After all, how do you know how far forward manufacturers have hedged?

Of course, a lot of suppliers don’t and can’t hedge. But even when they can and do, how do you know how far forward they have hedged? In the case of annual contracts on ambient goods like tinned tomatoes it’s reasonably straight forward. But in other areas some will have hedged for six months, and some as much as 18 months. And is a manufacturer really going to share that information?

No comments yet